Anthropic Philosopher Amanda Askell Details AI Prompting Techniques, Claude's Design

[Xinzhiyuan Guide] Amanda Askell, a philosopher at Anthropic, has been instrumental in shaping the personality, alignment, and value mechanisms of the Claude AI model. Her work also highlights effective prompting techniques, underscoring the relevance of philosophical training in the age of artificial intelligence. Professionals proficient in these prompt engineering skills can command a median annual salary of up to $150,000.

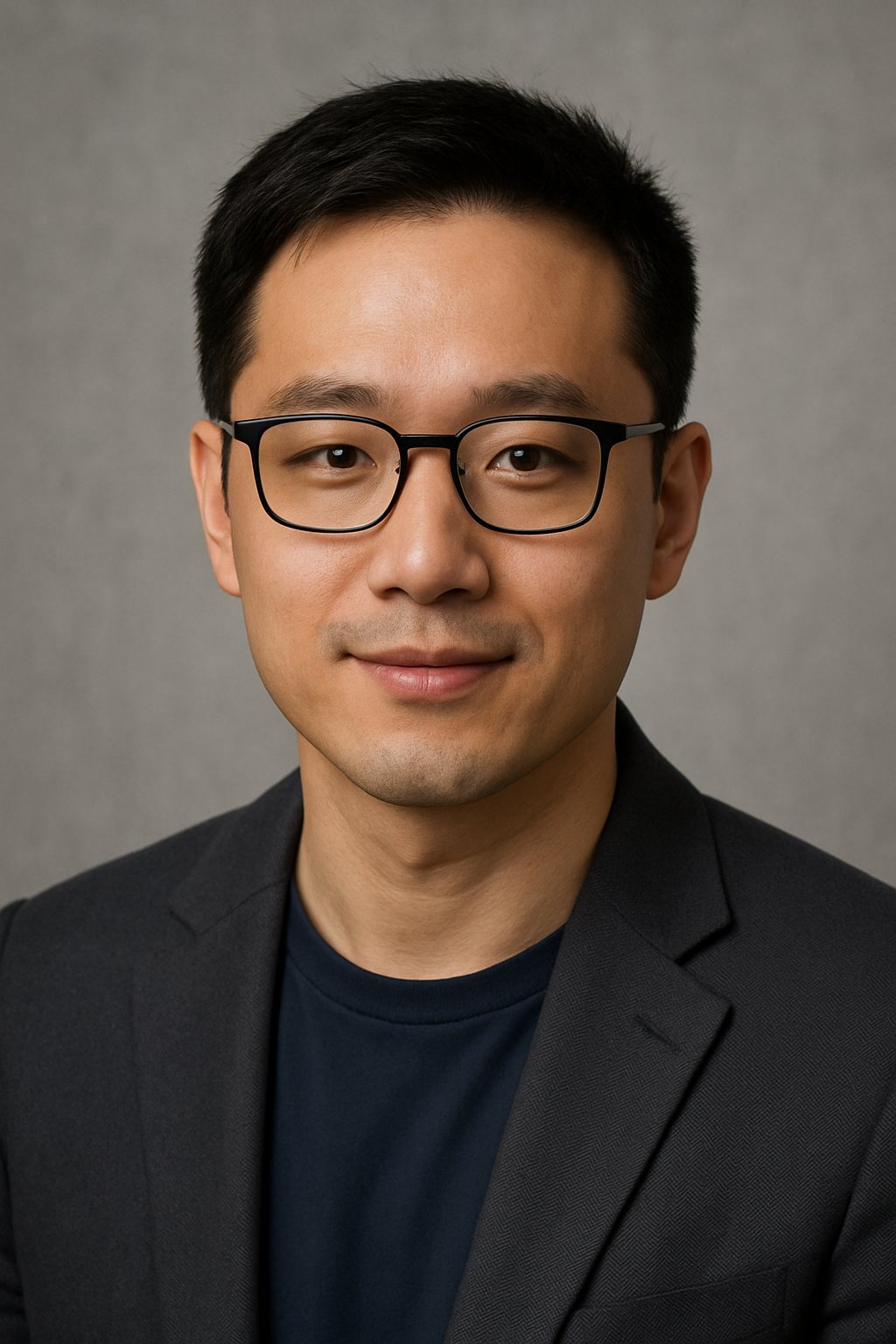

Askell, who holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from New York University (NYU) after studying at Oxford University, previously worked as a research scientist focusing on policy at OpenAI. She joined Anthropic in 2021 as a research scientist in alignment fine-tuning. Her responsibilities include instilling specific personality traits in Claude while preventing others. Askell was recognized among the "100 Most Influential AI People in 2024" for her leadership in designing Claude's core characteristics, earning her the moniker "Claude whisperer" due to her focus on optimizing its output through communication.

The "Philosophical Key" to Effective AI Interaction

Askell suggests that philosophy provides a crucial framework for interacting with complex AI systems. She recently shared her methodology for crafting effective AI prompts, emphasizing that prompt engineering requires clear expression, continuous experimentation, and a philosophical mindset. According to Askell, philosophy's core strength lies in its ability to articulate ideas with clarity and precision, which is vital for maximizing AI's utility. She noted that a key aspect of this process involves frequent interaction with the model and careful observation of its responses. Askell advocates for an experimental and bold approach to prompt writing, but stresses that philosophical thinking is more important than trial and error. She stated that a significant part of her role involves explaining problems, concerns, or ideas to the model as clearly as possible. This emphasis on clear expression not only refines prompts but also deepens understanding of AI itself.

Anthropic's "Prompt Engineering Overview" outlines several prompting techniques, including:

Being clear and direct.

Providing multiple examples (multishot/few-shot prompting) to illustrate desired output.

Asking the model to think step-by-step (chain-of-thought) for complex tasks to improve accuracy.

Assigning Claude a specific role (system prompt/role prompt) to establish context, style, and task boundaries.

This approach suggests that users should treat Claude as a highly intelligent but often forgetful new employee who requires explicit instructions. The more precise the user's needs are articulated, the better Claude's response will be. Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Netscape, echoed this sentiment, stating that AI's power lies in treating it as a "thought partner" and that "the art of AI is what questions you ask it." In the AI era, formulating the right question (prompt engineering) is often more critical than solving the problem itself, allowing humans to focus on questioning while AI handles problem-solving. This specialization contributes to the high salaries commanded by prompt engineers, with levels.fyi reporting a median annual salary of $150,000 for the role.

AI as a Simulator, Not an Entity

Andrej Karpathy recently advised against treating large language models (LLMs) as an "entity" but rather as a "simulator." He suggested that instead of asking an LLM what it "thinks" about a topic, users should inquire about which roles or groups would be appropriate to consult on that topic and what their perspectives might be. Karpathy explained that LLMs can simulate various viewpoints but do not form opinions over time like humans do. If a user asks a question using "you," the model may apply an implicit "personality embedding vector" based on statistical characteristics in its fine-tuning data, then respond in that persona. Karpathy's perspective aims to demystify the interaction with AI.

In response to Karpathy's view, user Dimitris asked if the model automatically adopts the role of the most capable expert. Karpathy confirmed this phenomenon, noting that a "personality" can be engineered for specific tasks, such as making the model imitate an expert or a user's preferred style. This can result in a "composite personality," which is a product of deliberate engineering rather than a naturally developed mind. Essentially, AI remains a token prediction machine, and its "personality" is an "outer shell" created through training, artificial constraints, and system instructions. Askell shares a similar view, stating that while Claude's personality has a "human-like quality," it lacks emotions, memory, or self-awareness. Any personality it exhibits is a result of complex language processing, not an inner consciousness.

The "Split-Brain Problem" in AI Development

Developing AI models can be challenging, often resembling a "whack-a-mole" game where fixing one issue can create others. Researchers at OpenAI and other institutions refer to one manifestation of this as the "split-brain problem": minor changes in question phrasing can lead to vastly different answers from the model. This problem suggests that current LLMs do not develop a gradual understanding of the world like humans do, potentially limiting their ability to generalize beyond their training data. This raises questions about the effectiveness of significant investments in AI labs like OpenAI and Anthropic, particularly regarding their models' capacity for novel discoveries in fields such as medicine and mathematics.

The "split-brain problem" typically emerges during the post-training phase of model development, when models are fed specialized data (e.g., medical or legal knowledge) or trained to improve user interaction. For instance, a model trained on a math problem dataset might become more accurate in mathematics. Simultaneously, training on another dataset might enhance its tone, personality, and formatting. However, this can inadvertently teach the model to "answer according to the scenario," where it decides how to respond based on its perceived context—whether it's a clear math problem or a general Q&A. If a user asks a math problem in a formal proof style, the model usually responds correctly. But if the query is casual, the model might mistakenly prioritize "friendly expression and beautiful formatting," sacrificing accuracy for these attributes, even including emojis. In essence, AI can "play favorites," providing "low-level" answers to perceived "low-level" questions and "high-level" answers to "high-level" ones. This "over-sensitivity" to prompt formatting means that subtle differences, such as using a dash versus a colon, can impact answer quality.

The "split-brain problem" highlights the complexities of model training, especially in ensuring the right combination of training data. It also explains why AI companies invest heavily in hiring experts in fields like mathematics, programming, and law to generate training data, aiming to prevent basic errors when models interact with professional users. The emergence of this problem has tempered expectations for AI's ability to automate multiple industries. While humans can also misunderstand questions, AI's purpose is to mitigate human shortcomings, not amplify them through issues like the "split-brain problem." Therefore, human experts with philosophical thinking and domain-specific knowledge are crucial for creating "manuals" for large model training and usage through prompt engineering. These "manuals" can help address the "split-brain problem" and mitigate machine hallucinations by preventing the illusion of treating LLMs as "persons." This underscores the value of philosophical training in fostering clear and logical dialogue with AI, suggesting that effective AI utilization depends more on philosophical thinking than on specialized AI knowledge for most users.